[고2] 2024년 09월 – 36번: 너무 유능한 사람은 오히려 덜 호감 가는 이유

It would seem obvious that the more competent someone is, the more we will like that person. By "competence," I mean a cluster of qualities: smartness, the ability to get things done, wise decisions, etc. We stand a better chance of doing well at our life tasks if we surround ourselves with people who know what they're doing and have a lot to teach us. But the research evidence is paradoxical: In problem-solving groups, the participants who are considered the most competent and have the best ideas tend not to be the ones who are best liked. Why? One possibility is that, although we like to be around competent people, those who are too competent make us uncomfortable. They may seem unapproachable, distant, superhuman ― and make us look bad (and feel worse) by comparison. If this were true, we might like people more if they reveal some evidence of fallibility. For example, if your friend is a brilliant mathematician, superb athlete, and gourmet cook, you might like him or her better if, every once in a while, they screwed up.

문제와 원문 출처 (링크 바로가기 클릭)

원문 출처 검색 불가

원문 텍스트 및 OCR

텍스트 비교 (문제 텍스트 vs. 원문 텍스트)

[고2] 2024년 09월 – 37번: 꿀벌의 춤과 컴퓨터 알고리즘의 차이

A computational algorithm that takes input data and generates some output from it doesn't really embody any notion of meaning. Certainly, such a computation does not generally have as its purpose its own survival and well-being. It does not, in general, assign value to the inputs. Compare, for example, a computer algorithm with the waggle dance of the honeybee, by which means a foraging bee conveys to others in the hive information about the source of food (such as nectar) it has located. The "dance" ― a series of stylized movements on the comb ― shows the bees how far away the food is and in which direction. But this input does not simply program other bees to go out and look for it. Rather, they evaluate this information, comparing it with their own knowledge of the surroundings. Some bees might not bother to make the journey, considering it not worthwhile. The input, such as it is, is processed in the light of the organism's own internal states and history; there is nothing prescriptive about its effects.

문제와 원문 출처 (링크 바로가기 클릭)

원문 텍스트 및 OCR

|

Similarly with the idea of life as computation. A computational algorithm that takes input data and generates some output from it doesn't really embody any notion of meaning either. Certainly, such a computation does not generally have as its purpose its own survival and well-being. It does not, in general, assign value to the inputs. Compare, for example, a computer algorithm with the waggle dance of the honeybee, by which means a foraging bee conveys to others in the hive information about the source of food (such as nectar) it has located. The "dance" ― a series of stylized movements on the comb ― shows the bees how far away the food is and in which direction. But this input does not simply program other bees to go out and look for it. Rather, they evaluate this information, comparing it with their own knowledge of the surroundings. Some bees might not bother to make the journey, deeming it not worthwhile. The input, such as it is, is processed in the light of the organism's own internal states and history; there is nothing prescriptive about its effects. |

텍스트 비교 (문제 텍스트 vs. 원문 텍스트)

considering = deeming

consider (v) 고려하다, 여기다, 생각하다

deem (v) ~로 여기다, 생각하다

[고2] 2024년 09월 – 38번: 행동 전염과 바이러스 전염의 유사점과 차이점

There are deep similarities between viral contagion and behavioral contagion. For example, people in close or extended proximity to others infected by a virus are themselves more likely to become infected, just as people are more likely to drink excessively when they spend more time in the company of heavy drinkers. But there are also important differences between the two types of contagion. One is that visibility promotes behavioral contagion but inhibits the spread of infectious diseases. Solar panels that are visible from the street, for instance, are more likely to stimulate neighboring installations. In contrast, we try to avoid others who are visibly ill. Another important difference is that whereas viral contagion is almost always a bad thing, behavioral contagion is sometimes negative ― as in the case of smoking ― but sometimes positive, as in the case of solar installations.

문제와 원문 출처 (링크 바로가기 클릭)

원문 텍스트 및 OCR

|

There are deep similarities between viral contagion and behavioral contagion. For example, people in close or extended proximity to others infected by a virus are themselves more likely to become infected, just as people are more likely to drink excessively when they spend more time in the company of heavy drinkers. But there are also important differences between the two types of contagion. One is that visibility promotes behavioral contagion but inhibits the spread of infectious diseases. Solar panels that are visible from the street, for instance, are more likely to stimulate neighboring installations. In contrast, we try to avoid others who are visibly ill. Another important difference is that whereas viral contagion is almost always a bad thing, behavioral contagion is sometimes negative—as in the case of smoking—but sometimes positive, as in the case of solar installations. |

텍스트 비교 (문제 텍스트 vs. 원문 텍스트)

[고2] 2024년 09월 – 39번: 동물의 동면과 수면의 차이

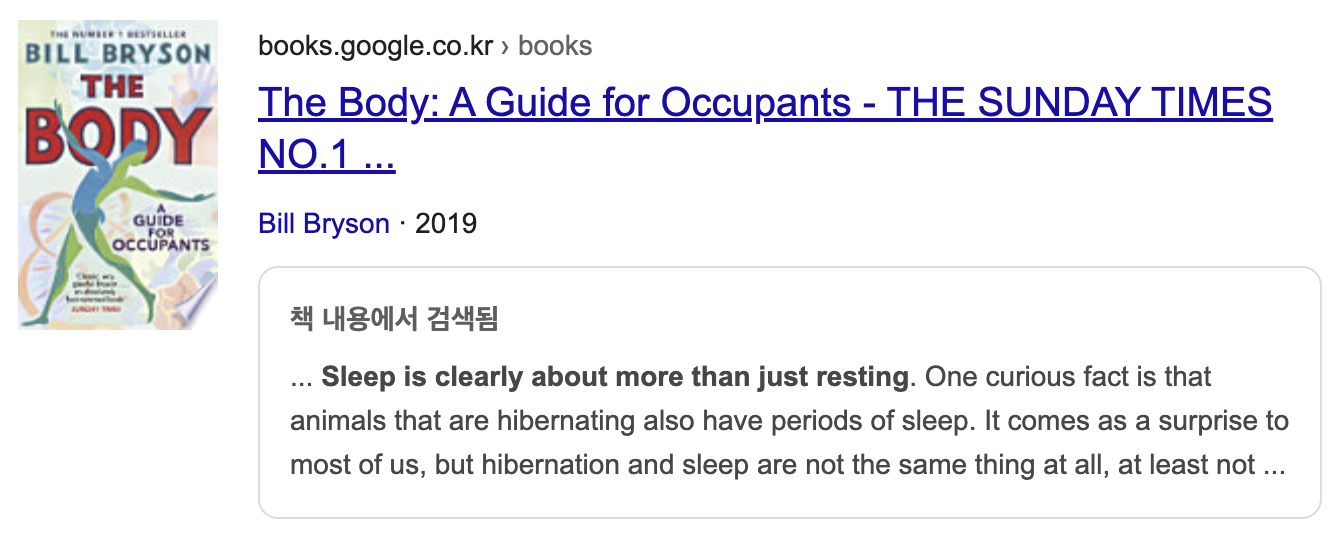

Sleep is clearly about more than just resting. One curious fact is that animals that are hibernating also have periods of sleep. It comes as a surprise to most of us, but hibernation and sleep are not the same thing at all, at least not from a neurological and metabolic perspective. Hibernating is more like being anesthetized: the subject is unconscious but not actually asleep. So a hibernating animal needs to get a few hours of conventional sleep each day within the larger unconsciousness. A further surprise to most of us is that bears, the most famous of wintry sleepers, don't actually hibernate. Real hibernation involves profound unconsciousness and a dramatic fall in body temperature ― often to around 32 degrees Fahrenheit. By this definition, bears don't hibernate, because their body temperature stays near normal and they are easily awakened. Their winter sleeps are more accurately called a state of torpor.

문제와 원문 출처 (링크 바로가기 클릭)

원문 텍스트 및 OCR

|

Sleep is clearly about more than just resting.** One curious fact is that animals that are hibernating also have periods of sleep. It comes as a surprise to most of us, but hibernation and sleep are not the same thing at all, at least not from a neurological and metabolic perspective. Hibernating is more like being concussed or anesthetized: the subject is unconscious but not actually asleep. So a hibernating animal needs to get a few hours of conventional sleep each day within the larger unconsciousness. A further surprise to most of us is that bears, the most famous of wintry slumberers, don’t actually hibernate. Real hibernation involves profound unconsciousness and a dramatic fall in body temperature—often to around 0°C. By this definition, bears don’t hibernate because their body temperature stays near normal and they are easily roused. Their winter slumbers are more accurately called a state of torpor. Whatever sleep gives us, it is more than just a period of recuperative inactivity. Something must make us crave it deeply to leave ourselves so vulnerable to attack by brigands or predators, yet as far as can be told sleep does nothing for us that couldn’t equally be done while we were awake but resting. We also do not know why we pass much of the night experiencing the surreal and often unsettling hallucinations that we call dreams. Being chased by zombies or finding yourself unaccountably naked at a bus stop doesn’t seem, on the face of it, a terribly restorative way to while away the hours of darkness. |

텍스트 비교 (문제 텍스트 vs. 원문 텍스트)

concussed

sleepers = slumberer

awakened = roused

concuss (v) 뇌진탕을 일으키다

concussed (a) 뇌진탕이 일어난

slumber (n) 잠, 수면 (v) 잠을 자다

slumberer (n) 잠자는 사람, 게으른 잠꾸러기

rouse (v) (특히 깊이 잠든 사람을) 깨우다

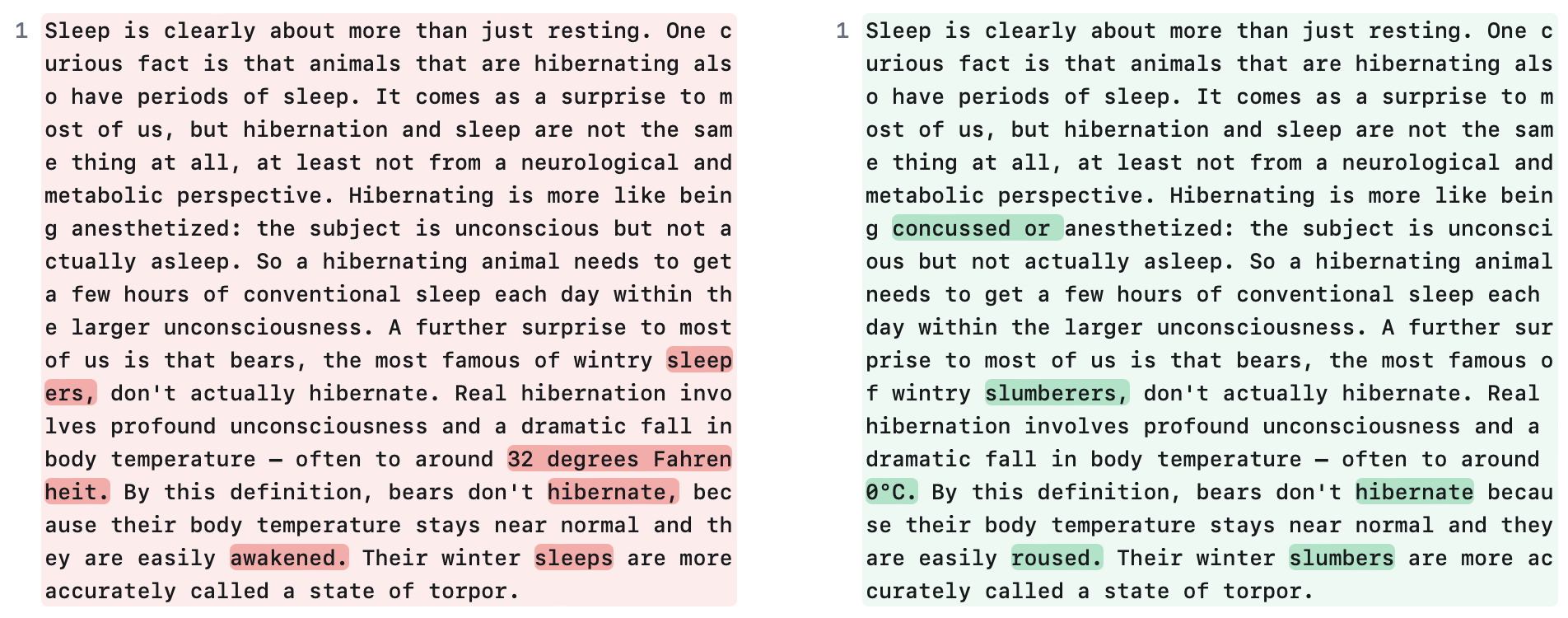

[고2] 2024년 09월 – 40번: 나이별로 타인의 평가를 의식하는 행동 차이

The concern about how we appear to others can be seen in children, though work by the psychologist Ervin Staub suggests that the effect may vary with age. In a study where children heard another child in distress, young children (kindergarten through second grade) were more likely to help the child in distress when with another child than when alone. But for older children ― in fourth and sixth grade ― the effect reversed: they were less likely to help a child in distress when they were with a peer than when they were alone. Staub suggested that younger children might feel more comfortable acting when they have the company of a peer, whereas older children might feel more concern about being judged by their peers and fear feeling embarrassed by overreacting. Staub noted that "older children seemed to discuss the distress sounds less and to react to them less openly than younger children." In other words, the older children were deliberately putting on a poker face in front of their peers.

문제와 원문 출처 (링크 바로가기 클릭)

원문 텍스트 및 OCR

|

This concern about how we appear to others can also be seen in children, though work by the psychologist Ervin Staub suggests that the effect may vary with age. In a study where children heard another child in distress, young children (kindergarten through second grade) were more likely to help the child in distress when with another child than when alone. But for older children—in fourth and sixth grade—the effect reversed: they were less likely to help a child in distress when they were with a peer than when they were alone. Staub suggested that younger children might feel more comfortable acting when they have the company of a peer, whereas older children might feel more concern about being judged by their peers and fear feeling embarrassed by overreacting. Staub noted that "older children seemed to discuss the distress sounds less and to react to them less openly than younger children." In other words, the older children were deliberately putting on a poker face in front of their peers. |

텍스트 비교 (문제 텍스트 vs. 원문 텍스트)

[고2] 2024년 09월 – 41~42번: 어린 시절 권위에 대한 질문의 중요성과 성인의 대응 방식

What makes questioning authority so hard? The difficulties start in childhood, when parents - the first and most powerful authority figures - show children "the way things are." This is a necessary element of learning language and socialization, and certainly most things learned in early childhood are noncontroversial: the English alphabet starts with A and ends with Z, the numbers 1 through 10 come before the numbers 11 through 20, and so on. Children, however, will spontaneously question things that are quite obvious to adults and even to older kids. The word "why?" becomes a challenge, as in, "Why is the sky blue?" Answers such as "because it just is" or "because I say so" tell children that they must unquestioningly accept what authorities say "just because," and children who persist in their questioning are likely to find themselves dismissed or yelled at for "bothering" adults with "meaningless" or "unimportant" questions. But these questions are in fact perfectly reasonable. Why is the sky blue? Many adults do not themselves know the answer. And who says the sky's color needs to be called "blue," anyway? How do we know that what one person calls "blue" is the same color that another calls "blue"? The scientific answers come from physics, but those are not the answers that children are seeking. They are trying to understand the world, and no matter how irritating the repeated questions may become to stressed and time-pressed parents, it is important to take them seriously to encourage kids to question authority to think for themselves.

문제와 원문 출처 (링크 바로가기 클릭)

원문 텍스트 및 OCR

|

What makes questioning authority so hard? The difficulties start in childhood, when parents—the first and most powerful authority figures—show children "the way things are." This is a necessary element of learning language and socialization, and certainly most things learned in early childhood are noncontroversial: the English alphabet starts with A and ends with Z, the numbers 1 through 10 come before the numbers 11 through 20, and so on. Children, however, will spontaneously question things that are quite obvious to adults and even to older kids. The word “why?” becomes a challenge, as in, “Why is the sky blue?” Answers such as “because it just is” or “because I say so” tell children that they must unquestioningly accept what authorities say “just because,” and children who persist in their questioning are likely to find themselves dismissed or yelled at for “bothering” adults with "meaningless" or "unimportant" questions. But these questions are in fact perfectly reasonable. Why is the sky blue? Many adults do not themselves know the answer. And who says the sky’s color needs to be called "blue," anyway? How do we know that what one person calls “blue” is the same color that another calls “blue”? The scientific answers come from physics, but those are not the answers that children are seeking. They are trying to understand the world, and no matter how irritating the repeated questions may become to stressed and time-pressed parents, it is important to take them seriously to encourage kids to question authority to think for themselves. |

텍스트 비교 (문제 텍스트 vs. 원문 텍스트)

관련 자료 바로가기

[고2] 2024년 9월 모의고사 - 지문 출처 (20~24번)

[고2] 2024년 09월 – 20번: 걱정은 통제 가능한 감정이라는 점을 자녀에게 가르치는 방법Merely convincing your children that worry is senseless and that they would be more content if they didn't worry isn't goi

flowedu.tistory.com

[고2] 2024년 9월 모의고사 - 지문 출처 (29~35번)

[고2] 2024년 09월 – 29번: 경제 중심 사고에서 생태적 건강을 중시하는 관점으로의 변화One well-known shift took place when the accepted view ― that the Earth was the center of the universe ― changed to one where we understoo

flowedu.tistory.com

'[고2] 영어 모의고사 자료 > [고2] 24년 9월 자료' 카테고리의 다른 글

| [고2] 2024년 9월 모의고사 - 지문 출처 (29~35번) (0) | 2024.09.14 |

|---|---|

| [고2] 2024년 9월 모의고사 - 지문 출처 (20~24번) (0) | 2024.09.13 |

| [고2] 2024년 9월 모의고사 - 지문 음원 듣기 (by ChatGPT-4o) (2) | 2024.09.10 |

| [고2] 2024년 9월 모의고사 - 지문 요약 by ChatGPT-4o (0) | 2024.09.06 |

| [고2] 2024년 9월 모의고사 - 한줄해석 (좌지문 우해석) (1) | 2024.09.05 |

| [고2] 2024년 9월 모의고사 - 한줄해석 (2) | 2024.09.05 |